When we visited AfriCat, the non-profit foundation that’s working to conserve Namibia's large carnivores, we didn’t expect to come face to face with the Adams family. But don’t go imagining black hair and pale skin; AfriCat’s siblings – Gomez, Morticia, Wednesday and Pugsley – are hairy with spots. They’re cheetahs who never knew their mother.

We were spending a day at the 200-square-kilometre private Okonjima Nature Reserve where rehabilitated cheetahs and wild dogs are given a second chance at a natural life. We’d been leopard tracking in the morning and now guide Martin Njekwa was telling us about AfriCat’s work and its motto of ‘conservation through education’.

One of AfriCat’s prime purposes is to promote environmental education to youngsters, who are the conservationists and farmers of the future. It also tries to educate farmers about wildlife and sustainability, and to resolve conflict between predators and communities.

For instance, AfriCat North – bordering Etosha National Park near Kamanjab – encourages community farmers to bring back cattle kraals and use herders to protect their animals from predators. AfriCat GPS-collars the dominant lioness in a pride or lone males that have left Etosha’s protected environment and moved into the Hobatere conservation concession or on to farmland south or west of Etosha. They can then monitor the lions and give farmers advance notice if the animals are moving through the area where their cattle are grazing.

Okonjima’s story, and that of the Hanssens who own the land, goes back three generations. From 1970 to 1990, the first generation was all about cattle farming and hunting. The second generation began what GM Shanna Groenewald calls ‘a concept of conservation’ that tried to save lives and develop tourism.

An example of this is Wahoo, a 17-year-old leopard that came here as an orphan so young his eyes weren’t even open yet. Back then, the second generation was still learning about conservation and their only thought was to save the cub’s life. But he was so little that he had to be bottle-fed so he became attached to humans. As a result he could never be released into the wild, but today he has 10ha of natural bush to call his own.

The third generation of the Hanssen family realised that such habituation wasn’t in the animals’ best interest. In 2010 the nature reserve was expanded to 20 000ha so that more captive carnivores could be released into a natural environment to start their rehabilitation. ‘In giving them a second chance we try to mimic as natural a life as possible,’ said Shanna.

Funded through tourism

Okonjima is a major funder of AfriCat, with tourism to the lodge also bringing in money for their work. ‘What’s different here is that we don’t rely only on donors, but fund AfriCat’s work through the lodge,’ she added. So just by visiting the AfriCat Day Centre or staying at the lodge you’re directly helping wildlife conservation. ‘This means there’s continuity of conservation, not waiting for more funds before we can take the next steps.’

‘However,’ the AfriCat Foundation’s Donna Hanssen pointed out, ‘although indirect funds through Okonjima’s tourism maintain roads and pay salaries and admin costs, it’s direct donations to the Foundation that allow the different projects to develop.’

When we visited Okonjima there were six free-ranging cheetah in the nature reserve. Others had arrived as a result of conflict on local farms, and they were hoping to release some of them into the nature reserve once they’d cleared more bush to accommodate them. Another four were released a few months after our visit.

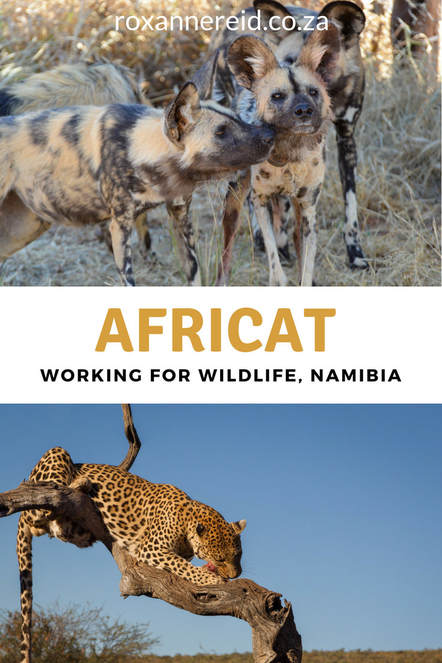

Wild dogs

Martin told us the story of seven wild dog pups rescued in 2005. They’d been buried alive after their parents were poisoned as a result of conflict with farmers. AfriCat saved them and tried to rear them, but it was difficult because when parents regurgitate food there are added nutrients that can’t be duplicated easily. Of the original seven only four were eventually successfully released into the Okonjima Nature Reserve in 2010, and only two females were still alive when we visited.

Against all expectations the remaining four claimed their first successful hunt just a month after their release – they dug a warthog out of its hole. The older dog remains the lowest ranking member of the pack, but regularly lies close to the three young siblings. ‘Constant monitoring of the pack’s movements and pack dynamics will tell if she’s accepted into the pack as a full member and if this attempt at introduction will ultimately be a success,’ said Donna.

Like it? Pin this image!