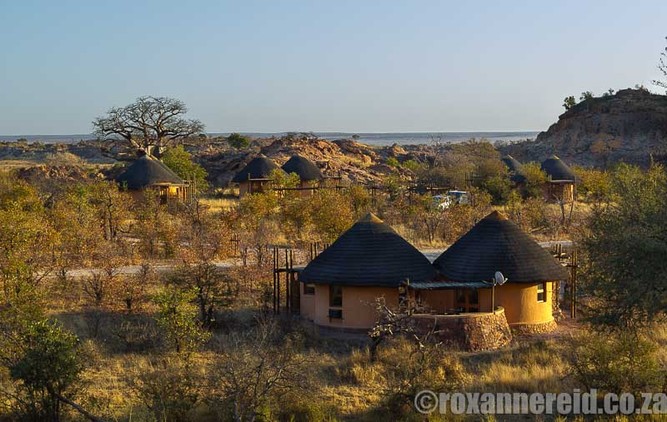

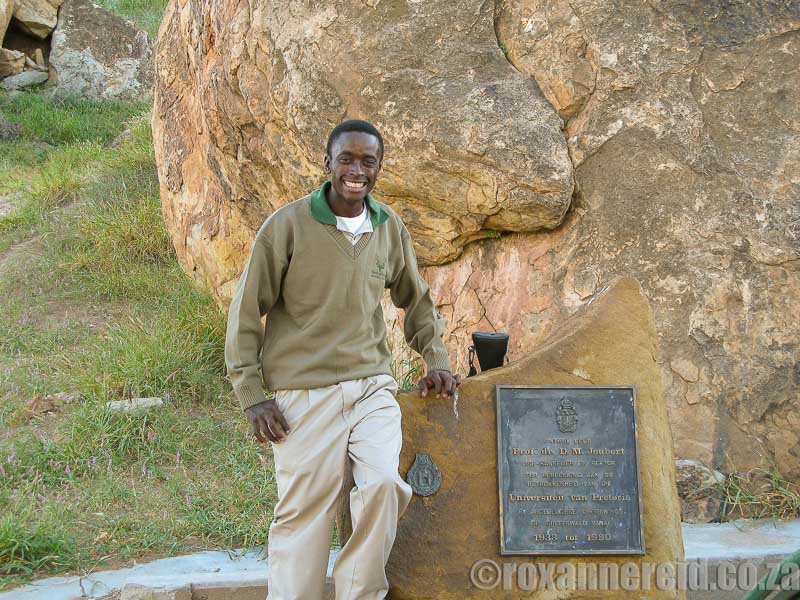

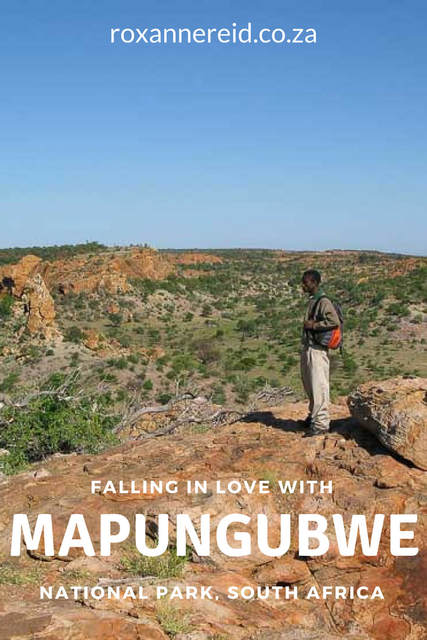

Seven years ago I found myself falling in love with Mapungubwe National Park on my first visit. Everything had me under its spell, from the enormous baobabs and gnarl-rooted fig trees clawing their way out of rock, to the red rock formations and the cultural history. So I was really looking forward to our second visit and hoping that guide Moses Baloyi would be there to share more about this place he loved.

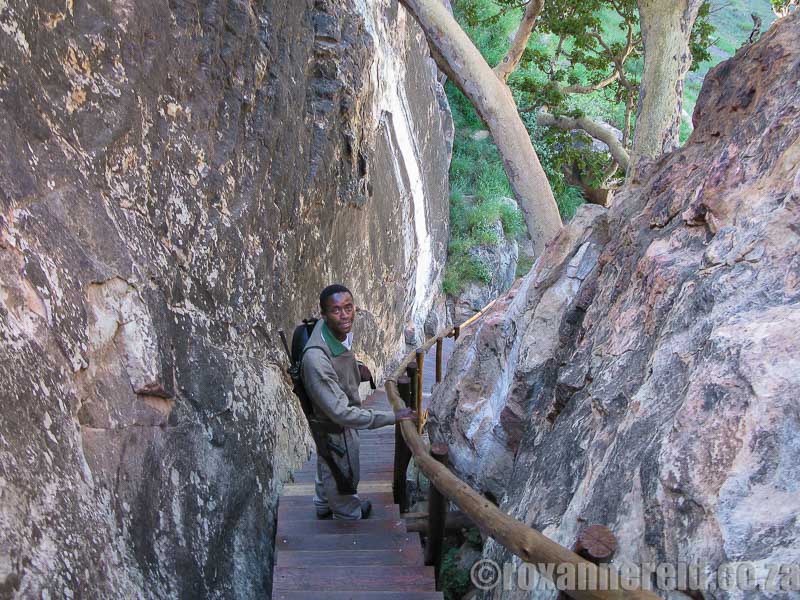

As a cultural guide to the famous Mapungubwe Hill, he had painted a vivid picture for us of women carrying clay pots filled with water on their heads, from the river, past a giant baobab and up the narrow pathway up the steep hill, step by rocky step. Or of a man in a leopard-skin cloak drinking a gourd of sorghum beer made from crops in the valley below.

Although Moses was a Shangaan (Tsonga) who grew up near Polokwane, his mother – a Sotho who grew up near Mapungubwe – remembered stories about the sacred hill and its mystery. Local African legend considers it taboo and people regard it with so much awe that they’ll turn their backs to it if you so much as say its name.

Ask Mokwena, the man who showed the way to the hill to the first archaeologists who plundered it in the 1930s, schlepping stuff off to Pretoria. Time and again he refused to show them where the hill was – until finally they plied him with enough booze to get him drunk. ‘Even then he stood with his back to it, and wouldn’t go up himself,’ says Moses.

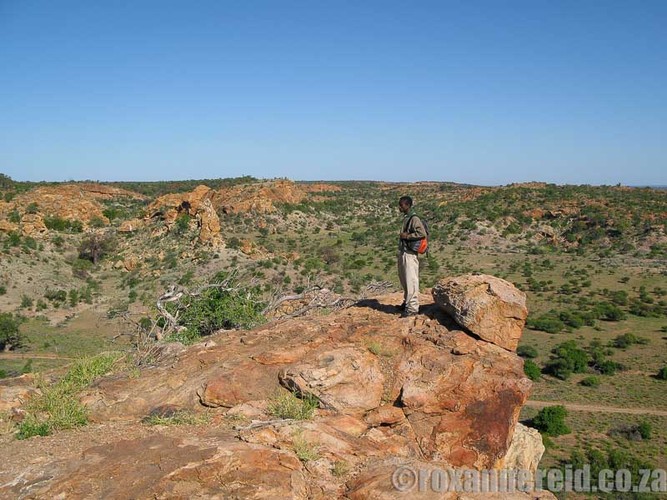

Mapungubwe Hill is 300 metres long, broad at one end, tapering at the other. About 50 people lived up here, with around 5 000 commoners at the foot of the hill. Some artefacts discovered on the summit include glass and gold beads, and the now-famous golden rhino with only one horn. Since African rhino have two, historians think it must have been traded with India, where the rhino have only one horn.

The people grew millet, sorghum and cotton and used to weave the cotton into rope. ‘The golden era of Mapungubwe was 1220 to 1250,’ said Moses. ‘After that they started to leave, probably due to climate change, which meant they couldn’t grow crops or feed their animals.’

Why is this a World Heritage Site?

‘First,’ explained Moses, ‘it was the forerunner of Great Zimbabwe further north.’

Second, it was the first southern African kingdom where the king and commoners were separated, the king isolated on top of the hill and the commoners below; the first class-based society in southern Africa.

Third, gold was discovered in the graves of royal families, evidence of trade with other parts of the world, probably Egypt, India and China.

Commoners, by contrast, were buried at the bottom of the hill, lying down, wrapped in animal skin and facing north. Some 200 such graves have been found down below, whereas just 23 graves have been discovered at the top of the hill. The bones and relics were removed to Pretoria years ago. On Goodwill Day in December 2005, 600 sangomas came to the hill to perform rituals to appease the ancestors and the remains have since been reburied on the hill.

Sadly, he didn’t live to see all the beads and jewels, the golden rhino, take up their rightful place in Mapungubwe’s magnificent interpretive centre when it opened in 2012. If he had, his smile would have been as bright as the sun that now lights up its stained glass windows.

Like it? Pin this image!

Mapungubwe National Park: everything you need to know

World Heritage Sites in South Africa and why to visit them

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without permission from roxannereid.co.za