You’ve had a hard morning’s game viewing when you arrive at the Kamqua picnic site on the Auob River in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park. You’re looking for a spot of shade where you can get out and stretch your legs. What you find is the lost city of the Kalahari & some dead trees.

I get that it’s a good idea to clear the vegetation under the trees, so snakes can’t hide there ready to nip visitors on the ankles. But I don’t know why a few of the park's staff couldn’t wield spades to skoffel off the offending growth. Instead, carelessly applied weed-killer has wiped out everything in sight, from the tiniest plant to large trees which – if left unpoisoned – could have lived for 200 to 300 years.

The Lost City of the Kalahari

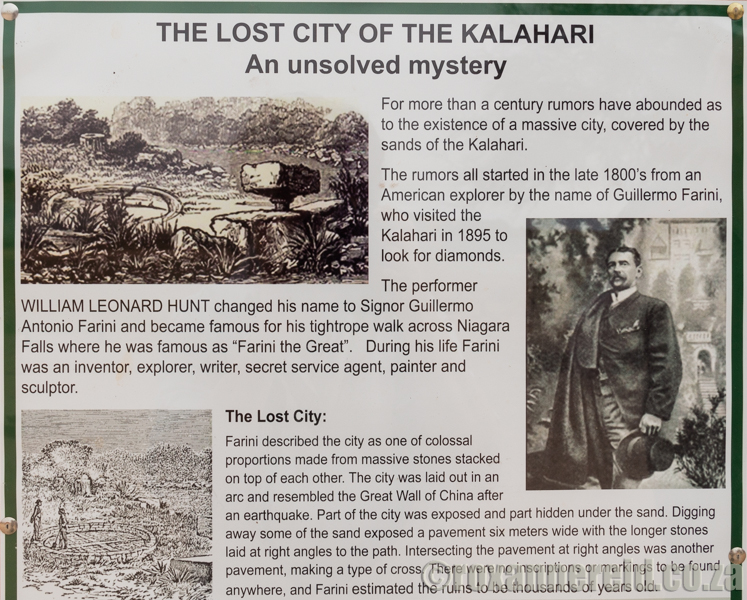

The legend about a vast city made from huge stones stacked on top of each other and then hidden away under the Kalahari sand has been knocking around for more than a century. Before you decide whether or not to believe it, you need to get to know the fellow who started the rumour.

He was one William Leonard Hunt, better known as The Great Farini – an explorer, inventor, writer, painter and spy, but best known for his tightrope performances at Niagara Falls in the 1860s. He was a fierce competitor and challenger of the more famous Blondin, and his exploits included crossing a high wire carrying a man on his back, or blindfolded, or with baskets on his feet, or doing somersaults along the way.

Definitely not an ordinary dude.

So what exactly did he find?

He wrote of ‘an irregular pile of stones’ he thought had once been ‘a huge walled enclosure’ about a mile long. ‘In the middle was a kind of pavement of long, narrow, square blocks neatly fitted together, forming a Maltese cross, in the centre of which at one time must have stood an altar.’

The city was laid out in an arc and looked a bit like the Great Wall of China after an earthquake. Part of it was exposed and part had been covered by sand. Not one to be deterred by his lack of archaeological training, Farini reckoned the ruins were thousands of years old.

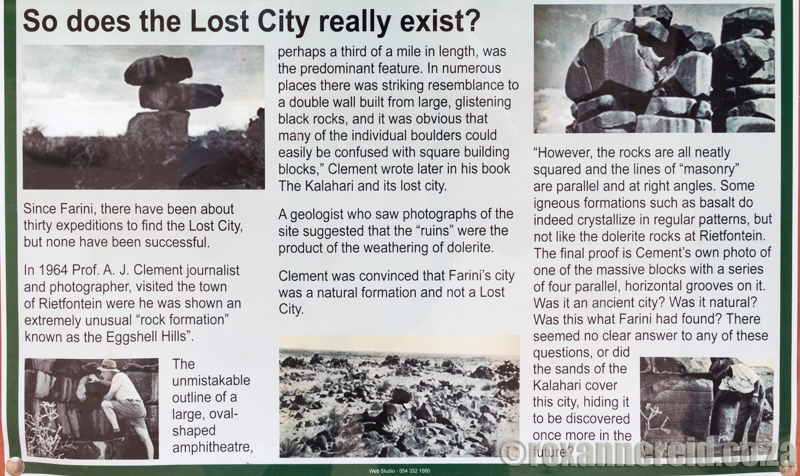

A geologist who saw photos of the site suggested that the ‘ruins’ were simply weathered dolerite. Magma intrusions had forced their way in and formed cracks and splits as it cooled. This is what made it look as if the rock had been carefully cut and dressed, with pieces stacked up on top of each other.

Clement agreed that the rocks were all neatly squared and the lines were parallel and at right angles. But he felt sure that if this was what Farini had seen, he’d seen a natural formation, not a lost city. ‘There’s something rather sad about the destruction of a legend,’ he added.

So despite the skeletons of dead trees, the Kamqua picnic site still has something to offer – but only if you stop to take in this tale of a mysterious lost city.

More about the Kgalagadi

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without written permission from roxannereid.co.za