If you care about wild animals and conservation in South Africa, you’ll want to read the book Rhino War: A General’s Bold Strategy in the Kruger National Park (Pan Macmillan 2022). It gives an insider’s view of what the struggle to prevent poaching of rhinos in Kruger has been like. Regular visitors to Kruger will recognise many of the places referred to, to add to their sense of ‘being there’.

In 2012, the job of creating a new and co-ordinated anti-poaching strategy for Kruger landed in the lap of 60-year-old retired South African army general, Johan Jooste. Back then, poaching was escalating fast, for reasons the book helps to explain. The challenge was to take disparate elements and create a unified paramilitary force that could act successfully against the poachers.

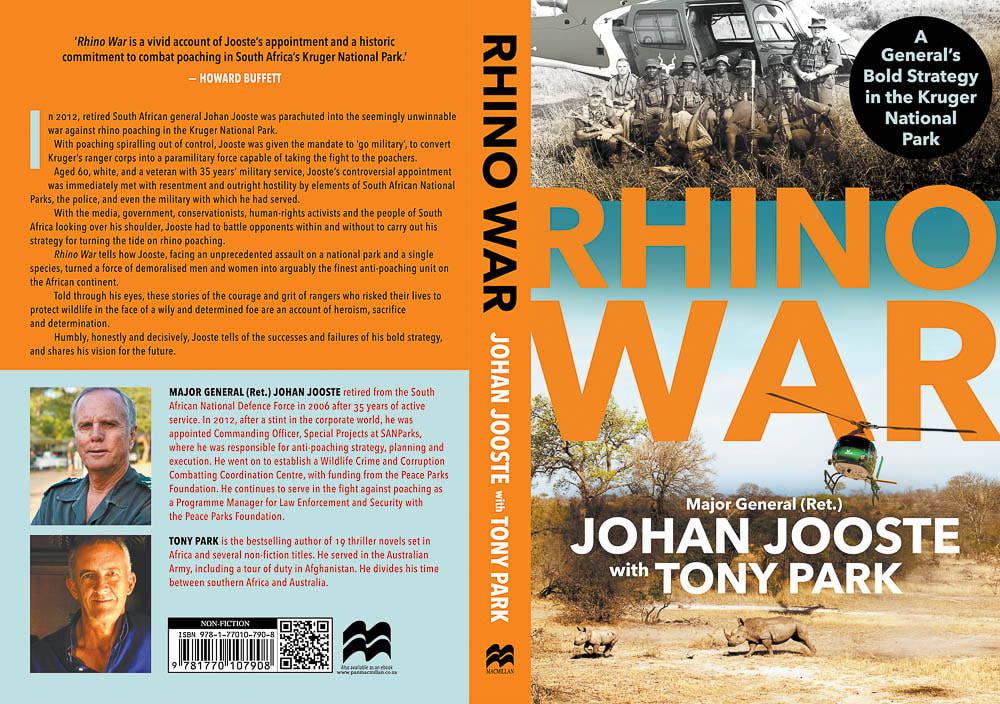

As the back cover blurb says, the book ‘tells how Jooste, facing an unprecedented assault on a national park and a single species, turned a force of demoralised men and women into arguably the finest anti-poaching unit on the African continent. Told through his eyes, these stories of the courage and grit of rangers who risked their lives to protect wildlife in the face of a wily and determined foe are an account of heroism, sacrifice and determination. Humbly, honestly and decisively, Jooste tells of the successes and failures of his bold strategy, and shares his vision for the future.’

I’m not much interested in all things military so I found the first chapter a bit slow, although I recognise that it was necessary to sketch Jooste’s background as a military strategist who would be able to use his skills in a new environment.

Insight into a horrifying scourge

The rest of the book is a fascinating insight into a deeply horrifying scourge of which we as the general public see only a small part. It doesn’t shy away from the dark side, admitting that some people in the park, the police and the army resented Jooste’s appointment while others were openly antagonistic. Add to this the fact that conservationists, government, the media, human-rights activists and South Africans in general were breathing down his neck, he was under a lot of pressure to succeed – and quickly.

In fact, one of the questions he kept getting asked at briefings and press events was: why isn’t there a drop yet in the number of rhinos being killed? If you read the book, it will start to make sense, given that the increasing number of kills played out against the backdrop of a dramatic surge in incursions into the park. The book goes into some of the reasons for this too, from poverty and increased demand for rhino horn in traditional medicine in the Far East to the dismantling of the border fence in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park.

He takes you through his strategic thinking, his analysis of what would be needed to win this ‘war’ against poachers. For instance, he determined that they needed more special rangers with improved skills, morale and weapons, as well as better evidence gathering and criminal investigation techniques. They needed to improve communications and investigate new technologies.

He also recognised that they needed to engage with Mozambique, where many of the poachers were initially coming from, and with private reserves on the western border of Kruger, so they could form a cohesive response. Ways of funding all this needed to be found too. There were some significant successes with this but he doesn’t sugar-coat the frustrations and failures.

‘Think big, start small and act now’

Jooste’s motto was: ‘You’ve got to think big, start small and act now.’ Acting now meant making the rangers into a force to be reckoned with, working as a tight team to face the poaching plague with the eventual aim of arresting poachers before they got a chance to kill a rhino for its horns. Technology could help with this. For instance, the CSIR-developed Meerkat ground-based radar system was used to such good effect that, just hours after it was first put into service, three poachers were arrested before they had a chance to kill a rhino.

Despite initial jealousies, suspicions and political roadblocks, there were lots of successes, with poachers caught by the streamlined, focused teams of rangers. Once the court at Skukuza started handling poaching cases – saving time and money – the system worked more efficiently too. Tracking dogs became game changers, with the number of dogs employed in Kruger by mid-2016 going up from just two to 52. ‘Within three short years,’ Jooste writes, ‘they had been involved in about 90% of all arrests in Kruger.’

I particularly enjoyed the parts of that book that describe how he improved ranger morale and gave them new pride in their work by listening to their concerns and supporting them in many different ways, as well as improving living conditions for them and their families. This quote strikes home: ‘From the air-conditioned comfort of the family car, or the elevated perch of a breezy open game viewer, Kruger is paradise. On foot, tracking a man who is prepared to kill to defend his ill-gotten prize is hell.’ How different life is for these hard-working men and women from what the average Kruger visitor experiences.

It’s no wonder, then, that despite their hunger for a sense of purpose and pride, they suffer from burnout and early symptoms of PTSD given the horrors they see and the life-threatening situations they encounter almost daily. To help them work through all this, psychological support was introduced.

Day in the life of rangers and pilots

A fast-paced series of pages written like a thriller novel describes a ‘typical’ day in which pilots and rangers on the ground were tested to their limits, with five back-to-back episodes of armed poachers having to be confronted. In four of them, they took fire but were nevertheless able to make arrests. This gives a small snapshot of the kind of stress these rangers and pilots are under.

It’s hard, as a wild animal lover, to read about the rhino orphans of these brutal poaching attacks being left to die in the early days because there was nowhere to take them to be looked after. But readers will relish learning about Kruger’s relationship with Care for Wild from 2014, a partnership that was to save the lives of rescued orphans and help safeguard the future of the species.

It’s also galling to read that the process of seeing an arrest through to a conviction – especially for high-profile kingpins – takes a frustratingly long time. ‘Some of these cases are still before the courts, years after arrests were made,’ notes Jooste.

Looking to the future

At the end of the book, he points to some possible future technologies that may prove useful in the fight against poaching. He also warns that various state departments are crucial to the success of the fight against poaching: ‘… without their buy-in and future success in collapsing crime networks, and further addressing community ownership and demand management, we will simply not progress from the current moderate win to a strong win. This fight cannot be left to the rangers, no matter how good they are or become.’

He ends with a wish that poaching could be controlled to such a degree that rangers will be able to go back to focusing their energy not just on rhino poaching, but on their core business – conservation.

I can’t say this book is an ‘enjoyable’ read given the subject matter. I did devour it in just three days, though, because it’s absorbing and enlightening. You’ll find it well worth reading if you have even a passing interest in the Kruger National Park, rhinos or African conservation in general.

The book should be available from Exclusive Books stores countrywide or from online retailers like Loot.

You may also enjoy

101 Kruger Tales: book review

Prepoceros rhinoceros: some facts about rhinos

Interesting facts about elephants at Letaba, Kruger

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without permission from roxannereid.co.za