Getting a safari guide to ourselves means we can indulge our interest in plants and stop to watch small creatures like lizards and birds. So we punched the air in triumph when we learnt our early morning drive was going to be a safari for two at Ngoma Lodge in Chobe, Botswana.

‘Elephants also destroy quite a lot of trees,’ said Bevan, a self-confessed lover of trees. ‘They strip the bark and eventually the tree dies. If they stop eating the bark of a baobab, the tree can heal itself over time. But if there’s too much damage it will die.’

Closer to the river we saw holes where elephants had been digging for salts in the clay beneath the Kalahari sand. ‘They like the clay because it has less grit so it doesn’t wear down their teeth,’ he explained. When they’re old and their molars are worn down they often die of starvation.

But the morning wasn’t all about elephants.

In the distance two men were fishing from a mokoro on the Namibian side of the river. The Chobe River forms the international boundary between Botswana and Namibia, an invisible border flowing down the middle. Fishing isn’t allowed on the Botswana side because this is a national park, but Bevan said sometimes people flout the law. We picked up a two-litre cold drink bottle floating on the edge of the river. At first it just looked like litter, but then we saw it had a short string and a fish hook attached to it.

There are some 450 species of birds in Chobe and we saw lots of them, including hamerkops and African jacanas mating – not something we’d seen in either species before. Helmeted guineafowl were more interested in clumping together to keep warm in the fresh early morning air. ‘When they do that, that’s when the martial eagle will take them,’ said Bevan.

A red-billed hornbill clung to a dead tree trunk as he fed his mate and her chicks inside a hole. Bevan explained how the female strips off all her feathers to make the nest inside the hole before laying her eggs.

The male brings mud in his bill to seal her in and keep her safe, leaving just a small slit through which he can feed her and the chicks. When the chicks are ready to fledge, he breaks through the mud and sets them free. Mother hornbill, her feathers now happily re-grown, also returns to the outside world and has to start finding her own food again.

On the drive back Bevan told us the story of a close encounter he had with a lion when he was working as a chef for a mobile safari company. The guide had taken their guests out for a game drive at Deception Valley in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, leaving Bevan behind to prepare breakfast.

‘I was all alone and a big lion was coming straight towards the camp,’ he said.

There was no vehicle to climb into. No weapon more threatening than a wooden spoon. ‘There was nothing I could do. I just watched it coming.’

Whether it’s the nesting ritual of a hornbill or a close personal encounter with a Kalahari lion, safari guides really do have the best stories.

Note: I was a guest of Africa Albida Tourism for two nights, but the opinions are mine. I paid for all travel costs.

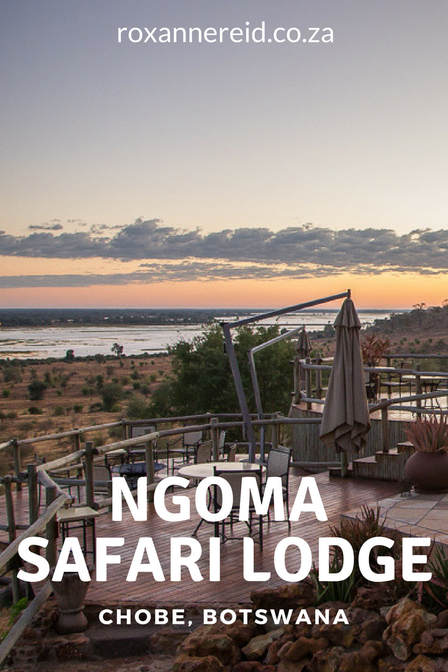

Like it? Pin this image!

Voices of Botswana: the tree man of Ngoma

Ngoma Safari Lodge, Botswana: a view to lust after

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without permission from roxannereid.co.za