We were passing through Kamanjab in Namibia’s Kunene district when we saw a Himba woman in traditional dress pulling a wheelie suitcase to the bus stop as if she was in an international airport – a strange jumble of two very different cultures. Now we were on our way to meet a whole village of Himba women and children but my dilemma over the clash of cultures was still prickling at the back of my mind.

He told us he wasn’t married; the bride price was three cows and he couldn’t afford even the cheapest cows that go for N$3000 apiece. (He did have a girlfriend and two children.) One of the three cows goes to the bride’s mother, one to her father and the last is slaughtered for the wedding feast. ‘One man might have 500 to 600 head of cattle and if he’s this rich he can have five or six wives,’ Ueera noted.

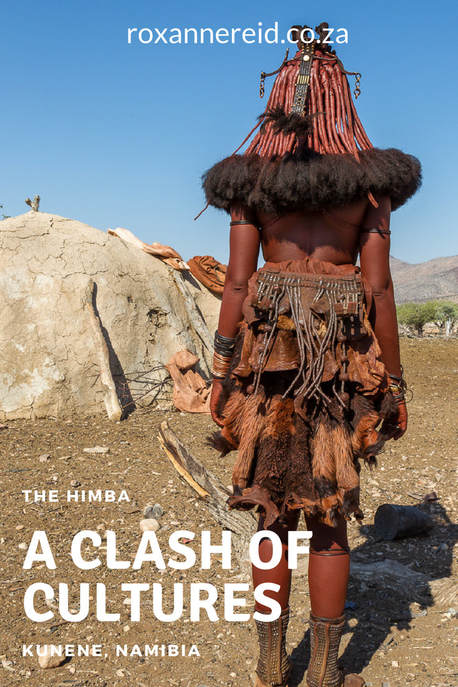

There’s an undeniable beauty and elegance about the Himba women that’s quite seductive, and probably explains why they’re in such demand among photographers both professional and amateur. For me it was more to learn about their culture, how to tell a girl from a woman, a mother from a woman who hasn’t yet had children.

Given the scarcity of water in this dry land, women don’t use it for washing. To clean her body, clothes and blankets, our hostess showed us how she used the perfumed smoke of burning aromatic plants and resins mixed with fat. She either bent over the perfumed smoke or covered herself with a blanket to trap the smoke underneath for a full smoke bath.

The day was searingly hot. We watched a woman skinning a baby goat that had died earlier that morning and it was already beginning to smell. It was a reminder not to romanticise their lives; no matter how elegant and beautiful the Himba women are, their life in this hot, dry area is a hard one.

We’d brought maize meal as a gift to exchange for their hospitality, and we bought some craft items the women had made to remember our visit by. But I’m conflicted. Such cultural interactions can be handled sensitively and with respect, but seeing firsthand how some of ancient traditions – think Vaseline and Indian-made hair braids – are already changing in the face of outside influence, I wonder whether the food and income we brought was enough to counterbalance the invasion of privacy, the inevitability of change.

‘Every culture has been eroded by somebody or something else,’ says Neil Shaw, project manager at a local non-profit organisation that helps rural entrepreneurs revitalise their communities through tourism that provides authentic experiences for travellers.

He’s referring to what they call living museums dotted around Namibia where the locals act out the traditional customs of their ancestors. ‘In the evenings it’s their choice to don a pair of jeans and watch a little TV. Why should this be any different for the Himba, or others?’

I understand what he’s saying and I hope that change can be on their terms, not imposed by what might be unwanted contact with outsiders. Isolation is what has kept the Himba culture and traditions intact over hundreds of years. Now it’s being chipped away little by little. So forgive me if I worry that my yearning to connect through such cultural interactions – whatever my intentions – might destroy the very thing that I find so beautiful, so different, so valuable. I’m not conceited enough to believe that everything Western civilisation can offer them is necessarily an improvement.

What do you think? Let me know in the comments below.

The Himbas have been the subject of countless photographs. A few years ago they turned the tables and decided to get behind the lens themselves to portray their life. The result was a short film called ‘The Himbas are Shooting!’ and you can see a trailer here.

Like it? Pin this image!

The Himba: the supermodels of Kunene

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without permission from roxannereid.co.za