He raised his rifle and pulled the trigger. Nothing happened. He ejected the cartridge and tried again. Nothing. Still the leopard rushed towards him, eyes locked on its target. There was time for only one more attempt before the animal was on him. But it wasn’t third time lucky for the leopard man of Limpopo, Ramolefe ‘Boy’ Moatshe.

Now, seven years since we met him, we’d returned to Marakele and heard the news that he had died. Although he’d have been in his nineties by now, we were saddened by the end of what had been one man’s remarkable story, which I documented in my book A Walk in the Park: Travels in & around South Africa's national parks.

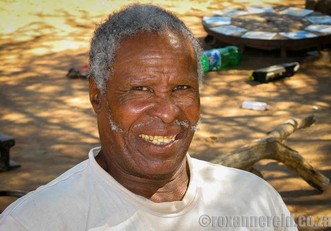

When we met him, Ramolefe limped with a walking stick and settled himself in a chair with evidence of the previous night’s fire at his back. Then he continued his tale in Afrikaans, in deference to our ignorance of Tswana. It was a story of incredible bravery, of survival against the odds way back in 1981.

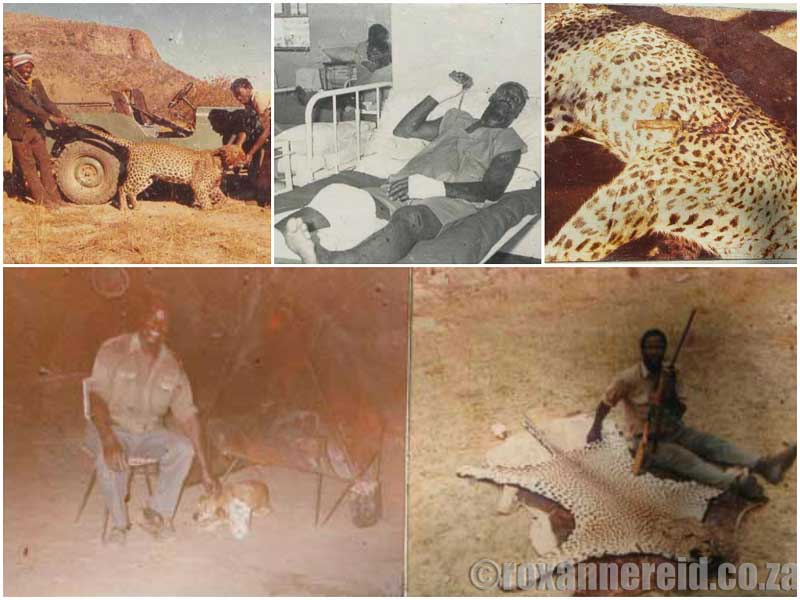

The big man tried to hit the leopard with the butt of the rifle as it attacked, but it bit through the wood as if it was butter. The two tumbled over one another down the mountainside into a dry river valley and landed on a flattish rock. Ramolefe knew he was outgunned without a leopard’s fearsome teeth and claws, but he was a strong man despite his nearly 60 years. The leopard struck the first serious blow, opening a cut on his head that started to bleed profusely.

By now Ramolefe was squishing in his boots. It was blood, he knew. Yet he fought on, battling with all his strength to gain the upper hand.

‘I wasn’t thinking about anything,’ he admitted. ‘Not winning, not dying there in the mountains, nothing.’ Pumped up on adrenalin, he was just reacting to the threat. ‘Then I remembered I had a homemade knife in my belt and I struggled to hold the leopard with one hand so I could grab it.’

Both adversaries were hampered by the slippery rock, the leopard failing at times to gain a foothold with its claws. Ramolefe too slipped and fell. By now both were exhausted and panting loudly. Finally, with the leopard on its side, he managed to stick the knife in once … twice. The animal snarled in pain. Blood seeped from its nostrils and mouth. A third thrust ended the 15-minute clash of wills and the leopard lay dead.

Piet helped his friend walk for some distance till they were almost in sight of their homes before Ramolefe collapsed. ‘There was no more power in me,’ he confessed. Piet set off to get help. ‘Hardloooooop!’ Ramolefe grunted, and Piet started to run.

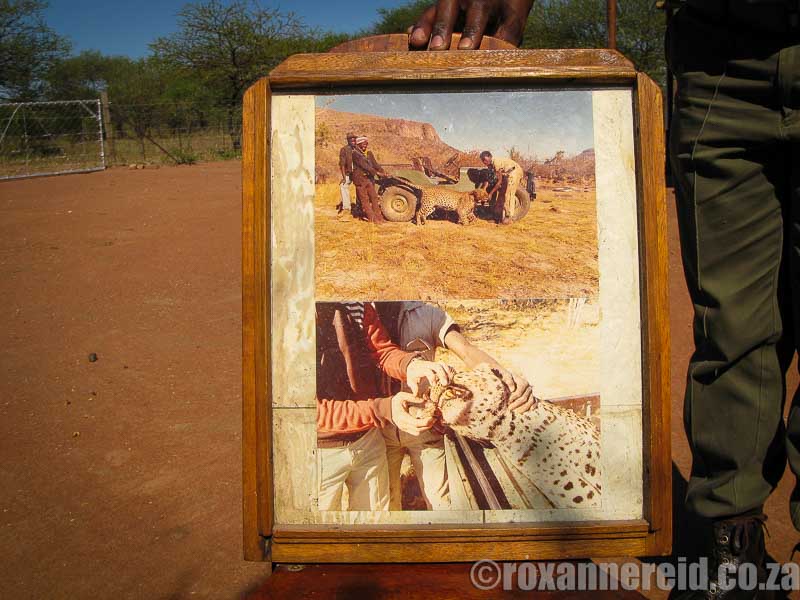

Piet raised the alarm and he and Ramolefe’s wife started an old Jeep to come back to fetch the injured man. It was a slow affair because neither could drive and all Piet could manage was first gear. An eternity later, they hoisted Ramolefe into the Jeep and limped and jerked to a shop not far away. Here was someone with a car and a licence, someone who could take him to hospital at Thabazimbi about 20 kilometres away.

But with an eye on the profits rather than the patient, the shopkeeper refused to leave until near closing time, so Ramolefe waited in a pool of blood. All he had to help him cope with his injuries, the shock and the pain was a Grandpa powder.

Within months he was back on the job, this time armed with a better gun – one that worked. ‘But I never needed to use it,’ he said.

The leopard had broken a tooth in the battle, and its claws had been worn down as it scrabbled about on the rocks. Now it was skinned and turned into a pelt that was initially given to Ramolefe, though he no longer had it. ‘My baas took it,’ he said simply.

Yes, those were the bad old days when you could nearly lose your life to protect your boss’s cattle from a marauding leopard, yet the pelt could be taken from you without so much as a backward glance.

In much the same way, Ramolefe accepted the lack of support from Piet during the attack. No recriminations, no enduring feud; he still saw him regularly.

‘He was a papbroek!’ I said, and he allowed himself two slow nods and a gruff chuckle. And with quiet laughter all round, we shook hands, honoured to have met a man who was a legend in his own lifetime.

Rest in peace, Madala.

You may also enjoy

Marakele National Park: everything you need to know

Mapungubwe National Park: everything you need to know

Like it? Pin this image!