Photo: Beate Schippert

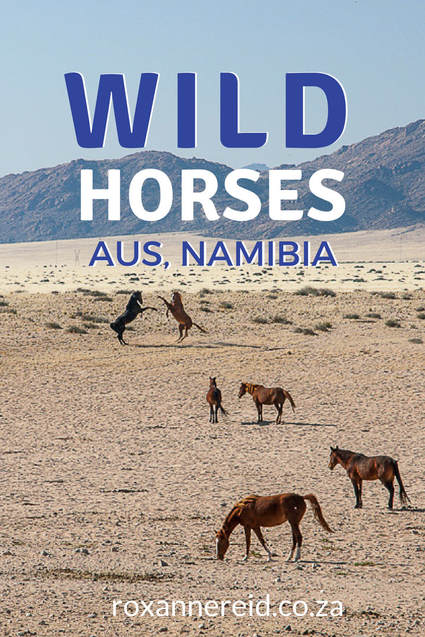

Photo: Beate Schippert In South Africa there are wild horses at Kleinmond in the Cape and Kaapschehoop in Mpumalanga. But it’s those in the Namib Desert that are the wildest and most romantic of all Southern Africa’s feral horses. The first time we went to visit the wild horses of Aus in southern Namibia, we had a number of questions. Where did the horses come from? How do they survive in this harsh environment?

Back then, in 2008, there had been excellent rains, so there was lots of grass for them to eat and they were fairly relaxed. When we returned in 2015, things were very different. What we saw was a blasted wasteland, not a blade of grass within sight of the waterhole. And that made us remember some of what Johann had told us about the difficulties for the horses in years of drought.

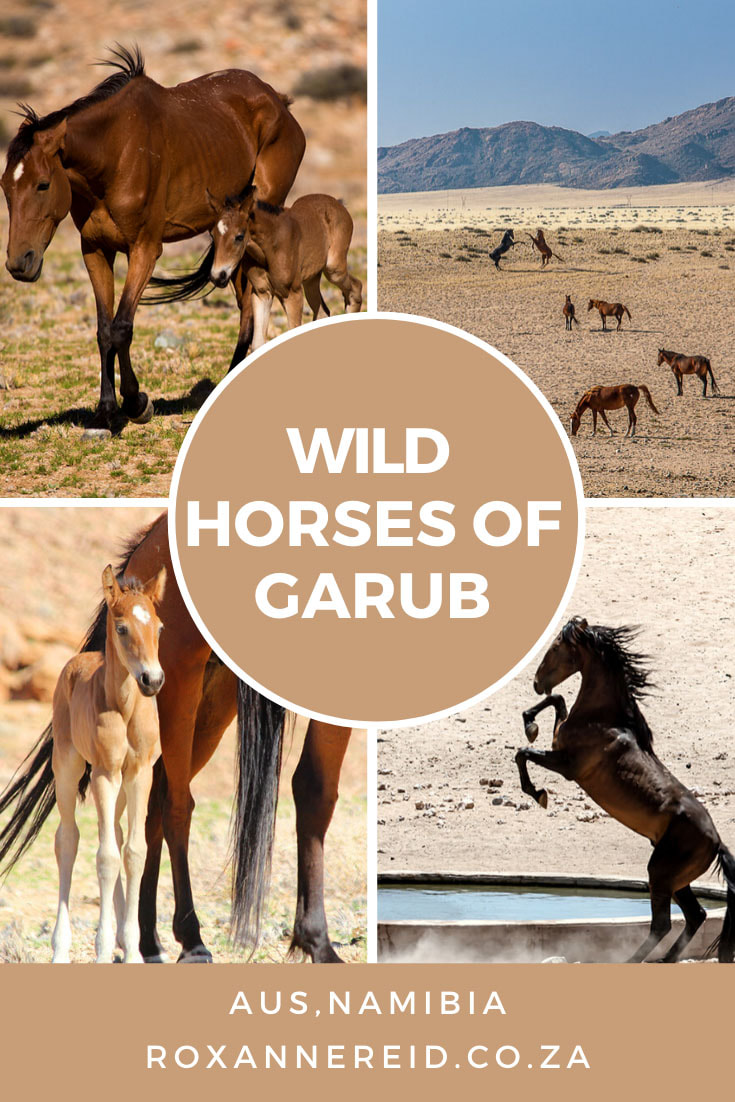

[Update November 2018] After years of having to be sustained during the drought by feed, the rains in mid-2018 broke the drought and covered the desert with a carpet of grass. By September 2018 the 79 surviving horses were fat and healthy. Even better, a foal had been born and more more expected. Given that not one had survived for six years, this was an event worth celebrating. Given that some hyenas moved out of the Namib Naukluft Park, there was hope that the new foal might have a fighting chance. But by November 2018, the hyenas returned with a vengeance, killing three of the four foals born since September, once again threatening the century-old population.

Where did the wild horses come from?

There were stories of wild horses already roaming the area in the mid 1920s. So where did they come from?

- One theory suggests they’re descendants of the horses of South African troops. Imagine it’s 1915 and the South African invasion into German-held territory is in full swing. The Germans have 1300 men at Aus, compared to the South Africans’ 10 000 troops and 6000 horses stationed at Garub nearby. But the Germans have a trick up their sleeves; they have three planes in the country and they decide to swoop in with a bomb. Not surprisingly, the horses bolt and scatter. Still vastly outnumbered, the Germans retreat. The South Africans, wanting to stay hot on their heels, perhaps don’t bother to catch the horses. And there you have the makings of a wild herd.

- Another theory relates to a stud that supplied the mines after the 1908 discovery of diamonds at Kolmanskop about 115km west of Aus. On his farm at Aus, Emil Kreplin bred work horses for pulling wagons at the mine and as racehorses for entertainment. The theory suggests that farmers chased these horses away because they competed with karakul sheep for water in an arid area and they became wild.

- Hans-Heinrich von Wolf, who built an incongruous castle in the desert at Duwisib, also used to breed horses for the German Schutztruppe (colonial forces). A third theory is that after he was killed at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, his wife opened the farm gates to set nearly 300 horses free into the desert.

The truth is probably a little bit of each of these – that the core herd were horses that belonged to the South African army, German colonial forces and the Kreplin stud (which also had connections to Duwisib). Left behind in the turmoil of World War I, these feral horses lived mainly in the restricted diamond area for the first 70 or 80 years, and that’s how they stayed out of the clutches of hunters and horse capturers.

Old photos show Kreplin’s horses had white markings on their backs, which can still be seen on the wild horses today, so a genetic link seems entirely possible.

Aus is on the southern edge of the Namib Desert, an area that usually has about 90mm of rain in a year. When we visited in 2008, there had been a whopping 200mm so the Bushman grass was as high as an elephant’s eye. Johann pointed to what he said were usually dunes, now well covered in a jacket of grass. ‘After really good rains it takes about 12 months for a good crop of foals,’ he said. ‘That’s three to four weeks for the grass to become good grazing and 11 months for gestation.’

This area is on the edge of three biomes so it enjoys both winter and summer rain. ‘But there was no rain at all in the late 1990s,’ Johann said. In 1992 there were 270 horses but the drought was so bad that 104 were captured and sold to be domesticated. In 1997 they rounded up more for auction but there was a public outcry so they let them go.

‘They’re very social animals,’ he explained, ‘and they’d been rounded up randomly rather than as families. This took a toll on the social organisation of the herds. By 1999 the drought was so bad there were just 89 left.’ By 2008 the population had bounced back to 165.

‘Back in the 1990s they were called the ghost horses because they were so seldom seen in those times of drought,’ said Johann. By contrast, after good rains in June 2008, we saw them just chilling around the waterhole because there was plenty of grazing close by. In such easy conditions, they adopt a ‘leisure mode’, using the spare time – saved by not having to walk long distances for food – to play and do a whole lot of resting.

One of the first adaptations these animals had to make to survive here in the wild was to tolerate levels of dehydration that would crush a domestic horse. Both temperature and how much grass there is to eat influence how often the horses come to drink at the Garub waterhole. When grass is abundant close to the waterhole, they’ll drink every day. When grazing is far away and temperatures are low, most will only drink every third day.

Another adaptation has been learning to conserve energy. Unless they have to travel far from the water to find grazing they just won’t budge – as we saw in 2008 when there was lots of tall grass near the waterhole that they could munch on around the clock if they wanted.

The grasses they eat lack salt so they nibble on calcrete stones to get salt. In addition, in dry years 7% of their diet is dung, a form of double-digesting that gives them twice as much protein and three times as much fat as the dry grass does on its first run through their digestive system.

Living here in this wide and wild expanse of desert, free to roam and form their own social structures, seems to suit the horses of the Namib. Even when they’re stressed by lack of rainfall (and therefore lack of grazing), as we saw in 2015 and has been the case in 2017, there’s less conflict than you might get from a herd of grumpy gemsbok, and fights between stallions seem more for show than genuine antagonism.

Above all, these horses are a symbol of the wild beauty of Namibia, the freedom of its wide and rugged landscapes.

The wild horses are under stress from the current drought (2015-18). To help maintain the wild horse population that is such a tourism draw card in this southern area of Namibia, please consider donating money to the Namibia Wild Horses Foundation, which uses funds for fodder supplementation and maintaining the water supply. Donate here.

Find it interesting? Pin this image!

Desert highlights of southern Namibia

Luderitz, Namibia: colourful hamlet in a windswept landscape

5 campsites in Namibia: the southwest

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without permission from roxannereid.co.za