Dry season in the Caprivi (now renamed the Zambezi) region of northern Namibia means lots of dust. But not everyone minds dust or even the wind that corkscrews it into the air. Certainly not the small boy in a bright yellow T-shirt who was happily playing with a tatty kite cobbled together from faded plastic supermarket packets.

It was a different Namibia.

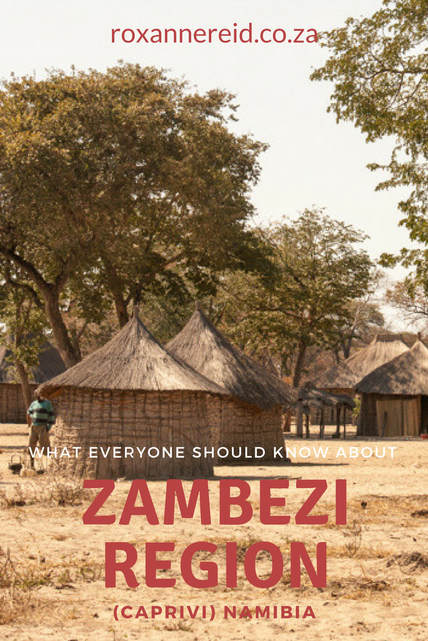

Namibia only has a population of about 3.5 million, but some 80% of them live north of the veterinary line. Small wonder, then, that there were thatched huts everywhere, their walls a lattice of tree branches filled with globs of mud, with neatly swept yards and allotments demarcated by thicker tree branches planted in the dirt.

In one yard an unexpected orange Range Rover, old and slightly the worse for wear; in another, bright shirts and dresses drying on the fence posts. Here a clinic, there a Baptist church. Donkey carts, two oxen pulling a cart laden with sacks, mealie cobs drying on roofs, neat groups of goats or cattle, skeletal winter trees with dried pods as bountiful as blossoms.

There was stuff for the local community too, like long cone-shaped baskets the locals use to catch fish in shallow waters. Or cash-and-carry depots of thatching grass so they don’t have to find, cut and bundle it themselves. And there were flags of red, blue, green and white fluttering in the light breeze. As elsewhere in Africa, I assume these are advertisements that the hut’s owner has something to sell, from meat to milk or maize.

We saw schools with neat dust playgrounds, here and there a China Shop, now ubiquitous in Africa, and lots of cuca shops – those tiny square brick-and-mortar buildings so well represented in Angola and here in northern Namibia. Cuca is a Southern African term for a shebeen, or unlicensed place selling booze. The name grew out of the Portuguese Cuca beer that used to be sold in Angola when it was still a Portuguese colony.

They flashed by as we drove: Ndina Shebeen, Come Together No. 1, the Moscow Shebeen night club and ‘Free Town’, a blue building with a faded sign, where five guys were lazing at a table under a tree enjoying a beer.

Dotted here and were red plastic loos, looking out of place against the monochrome background of huts and yards, more like London telephone booths. Amazingly, given the density of settlements which run into one another, and the mass of people, we saw almost no litter. It’s a hint of the poverty in the area, where nothing is thrown away because it may still have a use.

Indeed, there are plenty signs of the hardship of life here: about 40 plastic buckets of different colours and sizes gathered around a lone communal tap while women patiently wait their turn; small girls of six or eight with loads on their heads, doing the work of adults instead of playing as more privileged children can.

But there were also signs of carefree youth, like the little boy playing with his tatty plastic kite or a small clutch of kids dancing to the sound of a metal drum beaten with a wooden stick by a potbellied toddler.

A Ministry of Health bakkie stacked with cardboard boxes marked ‘Smile Condoms’ pulled out from the fuel pump, and an attendant filled our tank while holding his cell phone to his right ear with his left hand.

At another fuel station in the much smaller settlement of Divundu, the attendant hauled out a huge wad of R100 and N$100 notes to give us change. ‘Aren't you scared someone will attack you and steal the money?’ we joked.

He looked at us as if we were completely mad. ‘No,’ he said, perfectly serious, ‘because it's not their money.’

As if that was enough.

South Africa is so many miles away in both distance and philosophy. We could learn a few lessons here in rural Zambezi.

Like it? Pin this image!

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without permission from roxannereid.co.za