There isn't anyone more qualified to write a field guide to the animals, plants, climate and landscape of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park than Gus and Margie Mills, who have lived and worked there for 18 years. So when they produce a new natural history guide to the Kalahari, the book is sure to get a lot of attention.

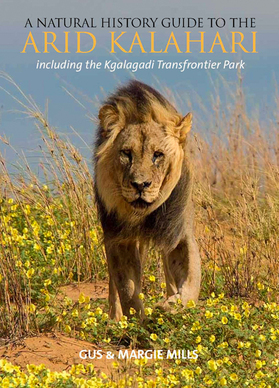

Their new book – A Natural History Guide to the Arid Kalahari including the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park – is 200 pages packed with information about this ‘land of huge vistas, climatic extremes and fascinating adaptations to harsh conditions’.

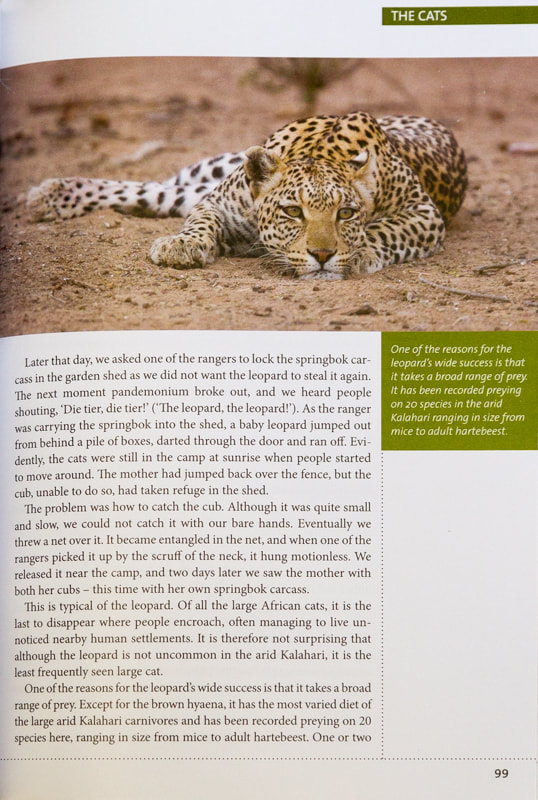

It covers some history about the development of the park, and describes its landscape, climate and characteristic plants. But by the main emphasis (six out of nine chapters) is on the animals that live there, from big cats, hyenas and other predators to antelope, birds and the secret life of smaller fry like rodents, amphibians and reptiles.

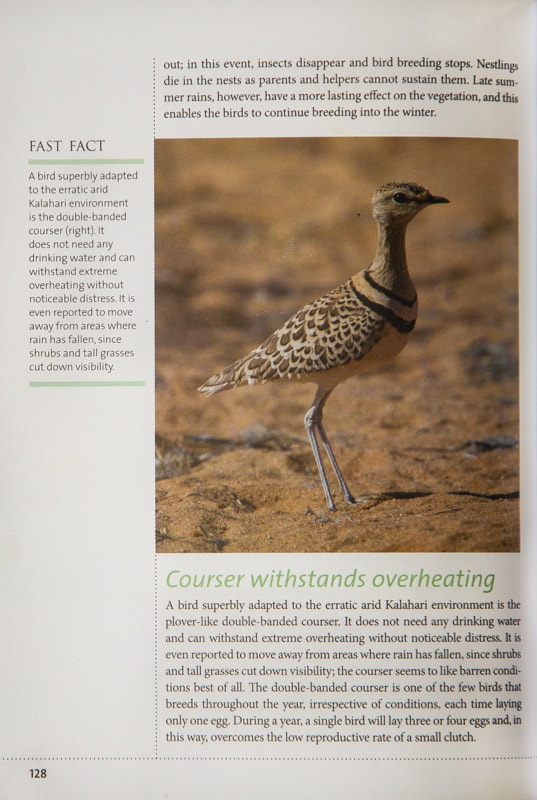

There’s a feast of photos with extended captions that provide information beyond merely identifying the animals or scene. For example, a photo of a springbok might tell you that the ‘fittest males set up territories along the riverbeds’, a photo of cheetahs on a kill will explain: ‘Cheetah male coalitions frequently kill young gemsbok through cooperation, but single cheetahs are unable to do so.

- It’s not true that the Kalahari lion is bigger than other lions; perhaps the openness of the habitat tends to exaggerate their apparent size.

- Scavenging does play a role in the spotted hyena’s diet, but in the Kalahari less than a third of their food is scavenged.

- Suricates (meerkats) are among the few animals that eat the large millipedes so common in the arid Kalahari after rain. The millipedes eject a defensive, repulsive fluid, but somehow the suricates can deal with this.

- Ostriches can lose up to 25% of their body weight when dehydrated, without suffering any ill effects. They can keep their body temperature normal in air temperatures of 51ºC for as long as seven hours.

- Bat-eared foxes are common during high rainfall years, but disappear during dry years; this seems to result from movement into the dunes and mortality.

- In recent years, the number of springbok along the riverbeds in the KTP has dropped markedly; it’s not clear whether human factors are responsible.

The final chapter gives advice on getting the most out of your visit to the arid Kalahari, with tips for travelling in the park, best time to visit and some game viewing strategies. There’s also a section on the Tswalu Kalahari Reserve, since the guide’s information applies as much there as it does to the KTP.

The A5 size is perfect for a field guide to take along on your next trip to the Kalahari, to dip into while you wait under a shady camel thorn or at a waterhole for some action.

The Mills’ long association with the park provides insight into its animals and ecosystems as well as a number of intriguing personal observations. Whether you’re a first-timer or you’ve been to the Kgalagadi many times, you’re sure to find lots to enhance your experience in this must-have guide for Kalahari lovers.

Where to get it

There’s been some frustration getting hold of the book after the publisher, Black Eagle, went into liquidation. However, you can sometimes find it at the shop at Twee Rivieren camp in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park. Or you can order it directly from the authors by emailing Margie Mills at [email protected]

You may also enjoy

Fast Cats on Red Sands: a must-read for Kalahari lovers

Hyenas of the Kalahari

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without written permission from roxannereid.co.za