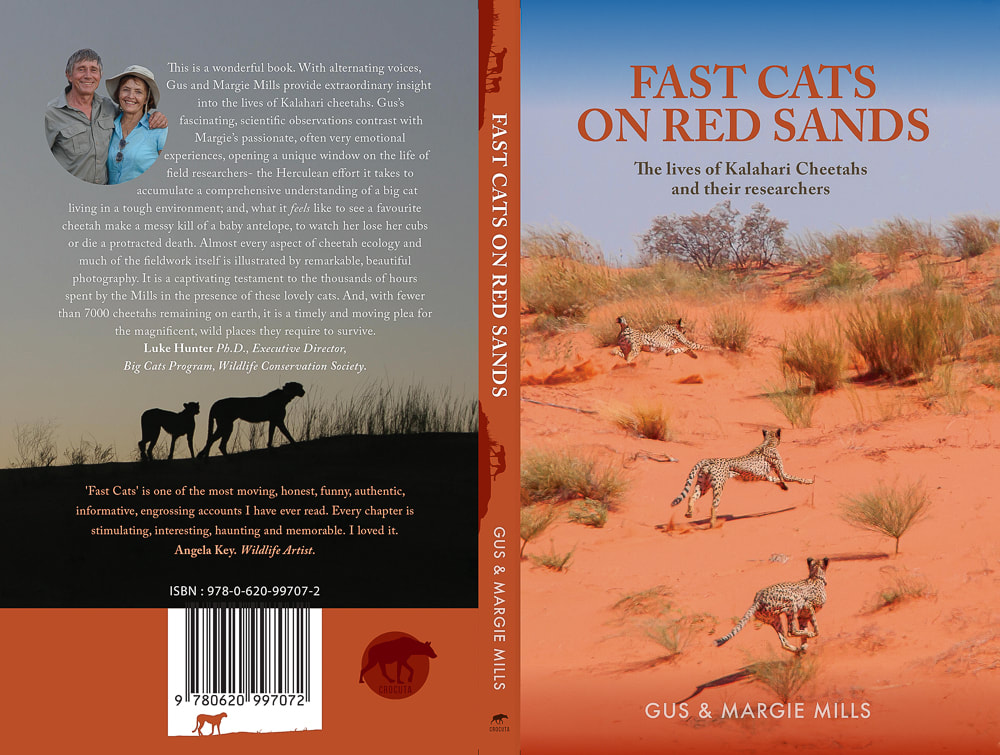

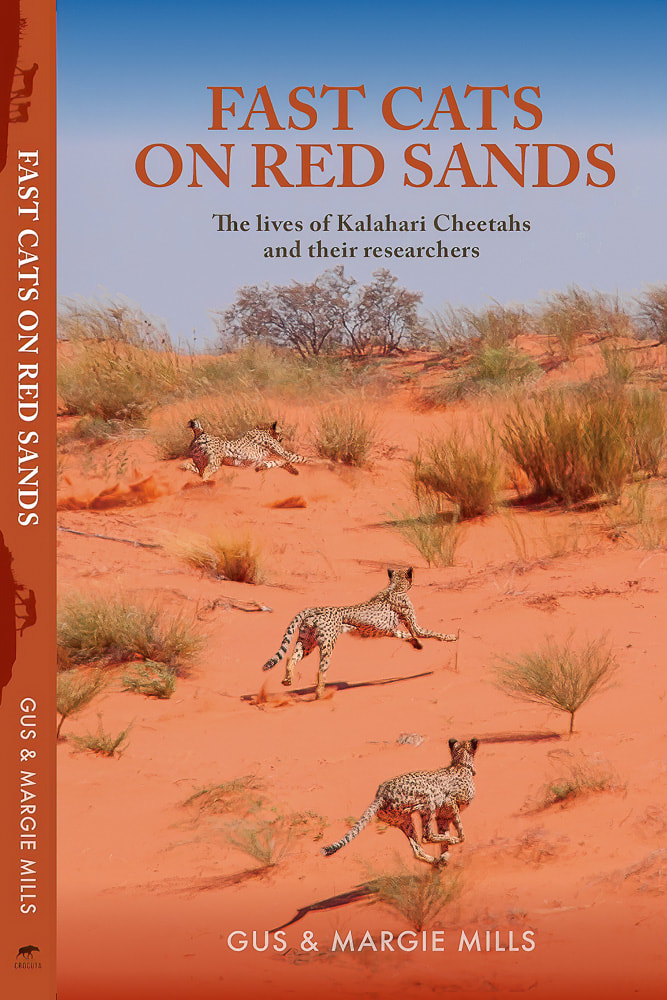

If you love wildlife and the Kalahari in general and the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park in particular, you’ll really love reading the recently published book Fast Cats on Red Sands: The lives of Kalahari Cheetahs and their researchers by Gus and Margie Mills. Read on to find out why.

First, let’s admit that Gus and Margie Mills are Kalahari boffins. They’ve spent 18 years living and doing research in the area, 12 years on brown and spotted hyenas and another six years studying cheetahs. Since no one had studied cheetahs in an arid system before, their research in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park from 2006 to 2012 was a chance to discover how these predators have adapted to an arid environment. And it makes for fascinating reading.

If you visited the Kgalagadi during those years, you may already be familiar with Gus and Margie because you met them along the road or supplied them with photographs of cheetahs so they could identify individuals by their spot patterns. (They identified 176 individuals in this way.)

Or perhaps you’ve devoured their Natural History Guide to the Arid Kalahari with its commentary on its creatures and landscapes, as well as tips for travelling in the park, best time to visit and some game viewing strategies. Our copy is already battered and tattered because it comes with us whenever we visit.

If you’ve read their book Hyena Nights & Kalahari Days about their time studying hyenas in the Kalahari Gemsbok Park – now the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park – from 1972 to 1984, you’ll know that they can communicate scientific information in a way that’s both engaging and easy for non-scientists to understand and appreciate. In Fast Cats on Red Sands Gus does exactly the same thing with the sciency stuff, making their observations and data easy to take in.

Margie threads personal insights through the book, telling us the joys and challenges of their lifestyle, how she felt when things went wrong. You’ll hold your breath with her, feel her angst and also her excitement.

Margie’s more intimate writing also reveals the characters of the scientists themselves, from soft-hearted Margie who blocks her ears or eyes to avoid heart-rending moments to pragmatic Gus who she describes as a ‘cheerful pessimist’ whose ‘light-hearted personality contrasts with his grave concern about the environment.’

This isn’t a large-format coffee table book, but a book to laze on a sun-lounger or couch somewhere to read and comb through for extraordinary insights into the lives of Kalahari cheetahs. The wealth of photos is an excellent backup to the text, depicting many of the amazing scenes and events Gus and Margie witnessed. These include both the positive – like the tiniest, cutest cheetah cubs you’ll ever see – to the upsetting, like cheetah-on-cheetah violence and death.

27 fact-filled chapters

Why should you care about cheetahs? In the past century, global cheetah populations have decreased substantially. They now occur in only 17% of the areas where they used to live, so their populations are vulnerable. They’re also wonderfully elegant cats, their sleek bodies and attractive faces making them probably my favourite wild cats.

In this book you’ll discover how well adapted they are for speed yet how, of the 7000 hours Gus and Margie spent watching them, the animals spent around 5000 hours (70% of the time) resting. Now imagine the fortitude the researchers had to have to spend six years following them and waiting patiently for things to happen.

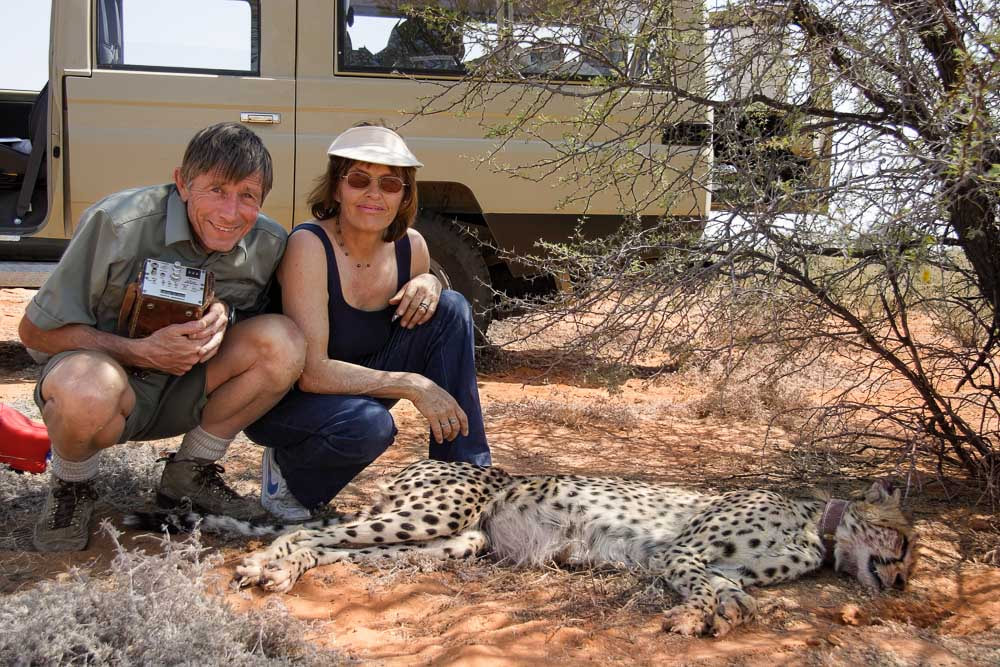

Tranquilising cheetahs to fit radio collars was their least favourite thing to do, but essential. They also at times used Bushman trackers to help follow cheetah spoor, combining this time-honoured method with more modern technologies like GPS navigation and the CyberTracker programme to record their data in the field. They squatted on all fours in the sand to collect hair with tweezers from places where cheetahs had been lying so they could have it analysed for DNA. This provided insight into genetic diversity and also the formation of male coalitions – for instance, that they don’t always consist of brothers as had previously been assumed.

And talking about hi-tech, Gus and Margie collaborated with scientists from an Irish university to measure energy use and water turnover by the cheetahs. This was tricky work involving, among other things, having to stay with a cheetah after a hunt/kill and to collect scat (poop) for analysis. It also meant having to be near the cheetah to collect the data logger when it was programmed to fall off its radio collar – something that needed huge patience and unfortunately didn’t always work as it should.

Despite the difficulties, this technology revealed facts the researchers wouldn’t have learned without it. Gus writes, ‘The energetics work we did is a great example of how a combination of traditional observational methods, together with state-of-the-art data logging hardware and software analysis, can uncover the complex nature of animal interactions. This should be a reminder to young scientists that technology without direct observations of the animals is like the internet without a connection, or a cellphone without data and airtime!’

I found the chapter on cheetah diet absorbing. Whereas you may have assumed that springbok was their main prey animal, analysing 539 cheetah kills showed that in fact steenbok made up 40%, hares 19% and springbok only 18%. There are also differences in diet according to whether the hunters are females, solitary males or coalition males. For instance, coalitions will take larger prey like young gemsbok and adult ostrich.

This chapter and especially the ones on predator-prey relationships might be upsetting for sensitive readers. But this is nature and, if you’ve visited game reserves often, you’ll already know how harsh it can be. As Margie writes, ‘I struggled when watching predators make a kill – I felt sorry for the prey, especially when it took a long time to die … [but] I felt relief when a female and her cubs, or a sibling group, made a kill after we had watched them going hungry for several days.’

Social interactions and mating

The authors also explore the topics of home ranges and dispersal of young cheetahs, and ‘the (not so sexy) sex life of cheetahs’. Little is known about cheetah mating and in nearly 100 hours they watched male and female cheetahs together, they only once caught a glimpse of them actually coupling. Piecing together other mating behaviour, they reveal that it’s very different from that of other cats. A female in oestrus will scent mark, there are ‘mating rendezvous areas’, and even coalition males try to get sole access to a female.

Looking at female reproduction, they observed that the radio-collared females they studied had cubs with them 62% of the time. ‘The average time between when a female either lost cubs prematurely or raised them to independence, to the time she gave birth again, was just under four months.’ Life is certainly tough for these single moms, who they dub ‘true heroes’.

There’s a section on purring and playing, with many delightful photos, and another on ‘Brawling boys – love feuds’ that opened my eyes to male-on-male cheetah aggression, something I’d known almost nothing about. Gus and Margie recorded 17 instances during their study and males died in 12 of these, more than half of the episodes directly caused by the presence of an oestrous female in the area.

Their study also looked at the genetics of cubs, determining who the fathers were. Surprisingly, there was little difference in the number of cubs fathered by coalition males and those by single males, and the success of two-male coalitions was actually greater than that of three-male coalitions. ‘This poses another conundrum regarding male coalitions: why should two related males join up with a third unrelated male? There seems to be no reproductive advantage to being in a three-male coalition.’

Don’t imagine that the challenges Gus and Margie faced related only to the cheetahs. The chapter called ‘It was not all beer and skittles’ tells about vehicle vulnerabilities like getting stuck in thick sand on the dunes despite Margie’s usually masterful driving – something that left Gus free to tend to the technology and the camera. Like a leaking fuel tank or multiple punctures – the record in a single day was eight punctures!

Once, when they were away, thieves broke into their house, stole alcohol and their research vehicle, taking it for a drunken joy ride before crashing, rolling and abandoning it, causing thousands of rands worth of damage.

For a look behind the scenes, Margie shares her thoughts on life with the Bushmen (a term they themselves prefer to San). Both she and Gus learned a lot from tracker Buks Kruiper and his assistant trackers. They greatly appreciated his interpretations of the tracks and signs he saw, helping them piece together what happened even when cheetahs had already left the scene. But in their interactions with the Bushmen they also had to contend with darker issues like TB, alcohol dependence and even murder.

The book highlights some intriguing new perspectives on old theories, for instance that not all cheetah hunts take place during the day. Also, although speeds during cheetah hunts of 95-122km/h have been tossed around, the maximum Gus and Margie measured in the Kgalagadi was 68km/h, with the average for the most hunted species – steenbok – being just 47km/h.

Also, despite assumptions about lack of genetic diversity in cheetahs, DNA analysis of 147 individuals in the Kgalagadi found quite the opposite: there is in fact little inbreeding in the Kalahari population because the area is so huge that males can move far away from their mothers and sisters.

The book ends with a practical commentary on how we can save cheetahs and ecosystems. A lot has been said and written about climate change but as Gus comments, ‘the root cause of climate change, and especially ecological devastation, is the growing human population and our ever-increasing consumption of natural resources.’ This chapter will reward slow reading and close attention to unpick the priorities he suggests for conservation in the here and now and in future.

Fast Cats on Red Sands is a book that will appeal to a wide variety of people, from big cat and cheetah enthusiasts to wildlife and animal lovers in general, from people who have fallen under the spell of the red sands of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park or wider Kalahari to those who still have it on their wish-list. Even if you’re not one for reading lots of text, you’ll appreciate the numerous photos and their explanatory captions. Conservationists and ecologists will find lots of useful, thought-provoking information.

If you think scientists are dry and dusty, you need to buy this book to discover how unpretentious and amusing they can be. Apart from finding a precious cache of cheetah facts that will heighten your understanding and pleasure when watching them in the wild, you’ll also enjoy the sections that give a window into the life of wildlife researchers, their trials and tribulations.

Where to buy it and what it costs

Order it directly from the authors by emailing Margie Mills at [email protected], who will give you the banking details. A bonus if you order from them directly is that Gus and Margie will sign your copy.

The book costs R280. If you live in South Africa, you’ll need to pay an extra R110 for PostNet to PostNet delivery (for up to 4 books). PostNet won’t deliver to your street address. Alternatively, you can have it couriered to your street address at R120 (for 1 or 2 books) or R140 (for 3-15 books). If you live outside South Africa, I hope you have a friend in South Africa who may be visiting you soon! Margie isn’t sending books out of South Africa because of the high cost.

If you’re lucky enough to be planning a visit to the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Augrabies Falls National Park or Kruger National Park in the near future, you’ll be thrilled to know that you should be able to find the book in their shops too, although these copies won’t be signed by the authors.

Interested in their other two titles? (See the two book reviews below.) You can order these directly from [email protected] as well.

You may also enjoy

20 reasons why you shouldn’t visit the Kalahari

Natural History Guide to the Arid Kalahari (book review)

Hyenas of the Kalahari (book review)

Like it? Pin this image!